I never met Johnny Mize. He left the party years before my family moved to this part of the world, where Johnny was born and raised and died. But I’ve spent the past few years getting to know him well, and I’m left with the impression that the Big Cat was a live-and-let-live kind of man. He may even have been a progressive thinker, ahead of his time in important ways.

For example, when Johnny was 20 years old and still a minor league baseball player, he spent the winter on Caribbean islands, playing ball alongside some of the best black and Latin ballplayers of all time. Here was a young man from the deep south, in the early 1930s, when separatist, racist lifestyles were the norm, and Jim Crow ruled the day, playing the part of a minority on a baseball diamond.

He didn’t see color on a ball field. He saw opportunity.

That is not to say that Johnny was a crusader for the rights of black baseball players. He was a pragmatist, not an activist. As a young player, he was still learning the economic and political ropes of baseball and realized that he had no power anyway, other than what he could generate with his bat.

This was the era of the reserve clause, long before free agency. Mize could barely control the route of his own professional destiny, and he wasn’t the type to step off that path.

But he was never the kind of angry ballplayer to stand in the way of racial progress, either. He wasn’t Dixie Walker or Ben Chapman or anything like the white supremacist crowd that ranted and raved about keeping baseball white. Mize just wanted to play ball and earn a few bucks.

Many years after he quit playing ball, when he was an old man, Johnny told a writer about the best ballplayer he’d ever seen. It wasn’t his cousin, Babe Ruth (who was old and past his prime when Mize saw him play). It wasn’t Joe DiMaggio or Ted Williams or Mickey Mantle, men that Johnny saw plenty of. Nope. It was a black Cuban man named Martin Dihigo, who managed the team Mize played for in the Dominican Republic, all those years earlier.

Mize saw Josh Gibson hit mammoth home runs, blasts that left him breathless. He recognized Gibson’s greatness. But he was unequivocal – Dihigo was far and away the best player he’d ever seen. He could pitch and run and hit for power. He left a lifelong impression on Mize.

Learning about Johnny’s early career, his days on the islands as a young man, gave me a greater appreciation of the Big Cat. He had this humanistic or cultural depth as part of his internal machinery, stuff I hadn’t really considered before when I set out to write a baseball book.

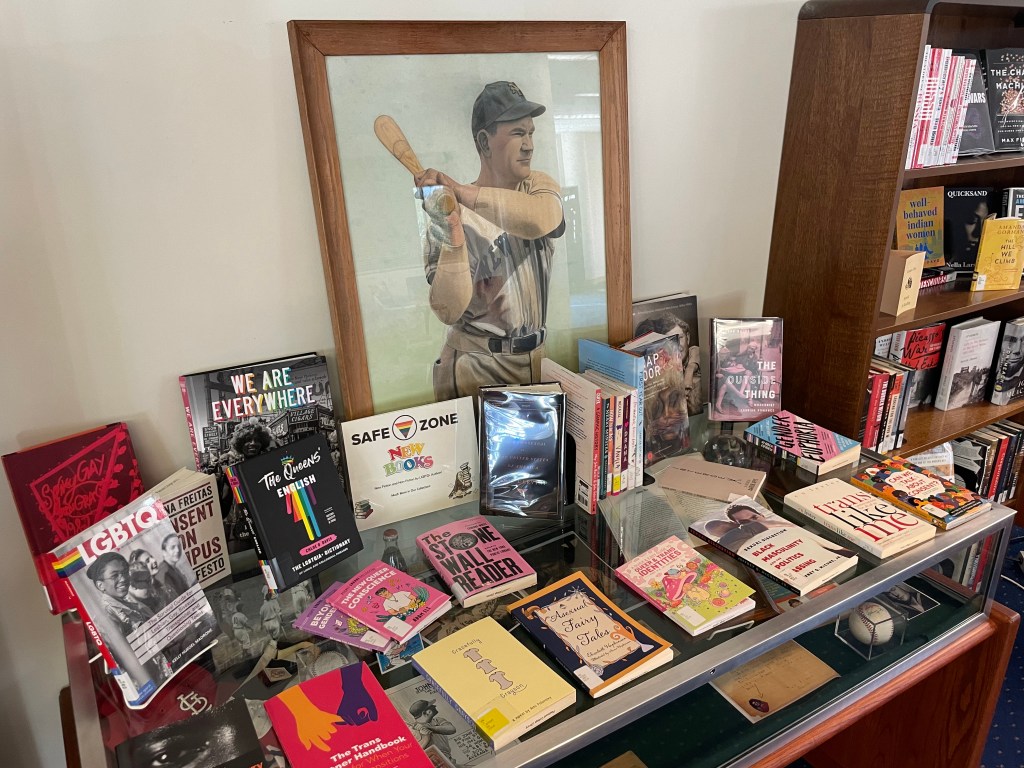

And then, not very long ago, I noticed how the good people at Piedmont University, Mize’s old school and stomping grounds, had adorned the Big Cat’s memorabilia display case in the school library. Look closely at the picture, at the books arrayed around the painting of Mize in his Giants uniform.

How completely wonderful, to my way of thinking, that the library would establish a “Safe Zone” for students, with new fiction and non-fiction by LGBTQ+ authors mingling with autographed photos and balls from a long-dead baseball legend. This isn’t a Hall of Fame. It’s a Hall of Awesomeness, and I like to imagine the enlightened ghost of Johnny Mize smiling and protecting this good space.