The business card was crumpled after living a few days in Dad’s fat and crowded wallet. In green, yellow, and black raised ink it said, “Holiday Inn,” and “Rose Calderone.” My father was basically the Johnny Appleseed of bowling for the Brunswick Corporation at the time. His official title was Regional Promotional Manager.

In the fashion of the famous fruit-loving folk hero, Tony Grillo spread the seeds of organized bowling leagues from Atlanta to Buffalo to Chicago to Dallas. And Brunswick’s profits grew, the key being linage (a way of measuring how busy the lanes have been in each bowling alley). The goal was to keep the balls rolling and those automatic pinsetters going, and the best way to guarantee that was to form bowling leagues, and Dad was really good at doing that.

Every week it was a different city. While he was in the Pittsburgh area, he stayed at the aforementioned Holiday Inn and met the proprietor, Rose, who was a childhood friend of the one and only Stan “the Man” Musial. This thrilled my father, who grew up on the Lower Eastside of Manhattan as a Yankees fan, later lived in Brooklyn, and remembered seeing Musial abuse Dodger pitchers in Ebbets Field. Dad loved Stan the Man. Everyone did.

Rose knew Dad was planning to see Stan play in an old timers’ game in Atlanta. “Give this to him, tell him you know me.” And that’s exactly what we did. Dad took me, my brother Steve, and cousin Matt. We presented the card to one of the field crew guys, who presented it to Stan, who was sitting in the dugout chatting with someone. I honestly can’t remember, but I hope that it was Johnny Mize.

And Stan came loping – so help me, he loped – out of the dugout to visit with us. My brother, cousin, and I shook the Man’s hand, chatted a while, got his autograph, and secured a lovely memory that we still enjoy sharing decades later. We returned to our seats about 20 rows behind the dugout, levitating part of the way. Dad sat there with a wide, “Did I deliver, or what?” smile on his face.

I’ve seen that smile in my mind so many times since. Thirteen years after our Musial meeting, Dad was nearing the end of his life. The last time we spoke together, his voice heartbreakingly weak, he recalled the day he introduced his boys to Stan Musial, when the greatest players of his generation gathered in Atlanta’s saucer-shaped ballpark.

It turned out that Dad was also a big Johnny Mize fan. I’ll never forget that day in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. As legend after legend was introduced over the P.A., Dad would comment on the guy, offering his first-hand information. The old timer he was most interested in, besides Stan, was Mize. As a lifelong Yankees fan, Dad loved seeing the Big Cat come to the Bronx in 1949. Considered all but washed up in the National League, he was discarded by the impatient (and impudent) Leo Durocher, manager of the Giants, a team Mize had been with since 1942, before the war interrupted his career, and for whom Mize had set unbreakable home run records.

In August of 49, Casey Stengel brought Mize over the Harlem River from the Polo Grounds to Yankee Stadium. He wanted Mize’s bat for the stretch pennant run. The Yankees battled the Boston Red Sox down to the last day of the season. Johnny had a few clutch hits before injuring himself, then delivered a huge RBI single in the World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers – a hit that Stengel called his favorite highlight of the 1949 season, his first as Yanks skipper. Dad remembered all of that, and he remembered the subsequent four seasons, when Mize became known as the best pinch hitter in the American League.

Dad always loved an underdog story, and Johnny Mize was special to him. “They thought he was finished when he came to the Yankees from the Giants in ’49,” Dad said. “Then he became the best pinch hitter in baseball. Without Johnny Mize, the Yankees don’t win five straight World Series.”

As I was writing “Big Cat,” my biography of Mize, it was impossible not to keep recalling memories of my father, the first baseball fan I knew and the man whose influence led to my ridiculous affection for the old game. Dad knew exactly what he was doing when he gushed about having seen Gehrig, DiMaggio, Berra, Mantle, as well as Musial, Robinson, Mays, Campanella. And Mize. Dad knew his stories sounded like mythology to me, knew that these were irresistible adventures to my young ears. He had my attention, and Dad could always work an audience.

Anyway, I always knew that this book would be dedicated Dad and Mom. Here’s what I wrote about them in the acknowledgements:

“Dad, who took his backstage pass to the universe in 1987, is the reason that I’m a baseball fan. But it was his appreciation of the game’s improvisational drama and action, his love of the characters and humanity—the heroes and the villains—that kept him interested and continues to keep me interested. And Mom may not be a devoted baseball fan, but she loves The Pride of the Yankees and Field of Dreams, and she always supported my passion for a ridiculous game. When I was 13 or 14, mom surprised me with a lovely thing she quietly made. She took the Hank Aaron autograph that I’d recently acquired, cut out magazine photos of Aaron and other players, and built a collage around the signature, then framed it. I’m looking at it now, hanging the wall above my computer screen, while typing these words. Thank you, Mom and Dad for always making me feel so loved, lucky, and inspired.”

And a coda: I also spent a lot of time thinking about the father-son relationship in general, while writing the book. Because Mize didn’t have a father in his life. He basically came from a broken home. His mother lived in Atlanta while Johnny was raised in Demorest by his grandmother and aunt. Then, when he married his second wife, who had two young children, Mize had to learn how to be a father. Based on stories from his son Jim, it wasn’t always easy. His daughter, Judi, adored the Big Cat. She had him wrapped around her little finger. But it was work for Mize, who didn’t have anyone to model.

Then again, neither did my dad. His father was a scoundrel that my grandmother was brave enough and wise enough to leave (while pregnant with Dad, the youngest of seven Sicilian-American kids). So, Dad didn’t have a model, either. But he absolutely adored his role as the father of five.

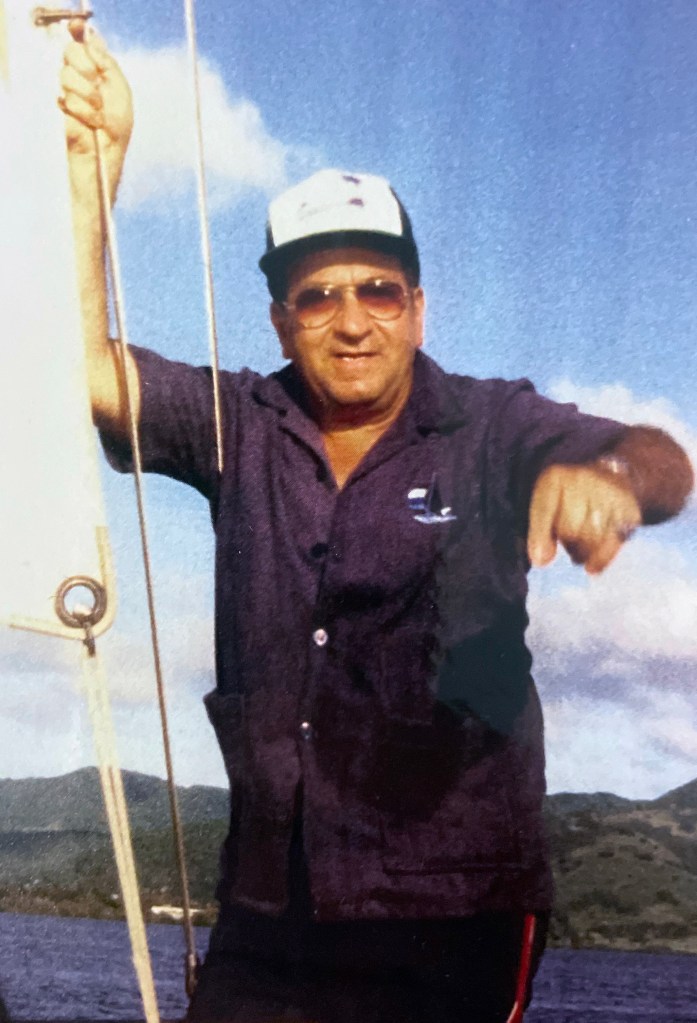

My old man was never much of a bowler, even though he could sell the game. And he wasn’t a great ballplayer (in spite of his tall tales to the contrary, that he joyfully told, feigning hurt feelings when we laughed and made fun). Oh, he was strong and could throw hard with his odd, halting throwing style. But he was never going to take someone’s place in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Now, if there was a hall of fame for fathers, I believe he’d have a dedicated wing.