Bob Oliver’s 1973 card is one that I’d subconsciously uploaded into my memory bank years ago. The second I plucked it from the box it went like this: “Oh, yeah – the cool action shot of Oliver reaching for the throw at first while Bert Campaneris speeds down the baseline.”

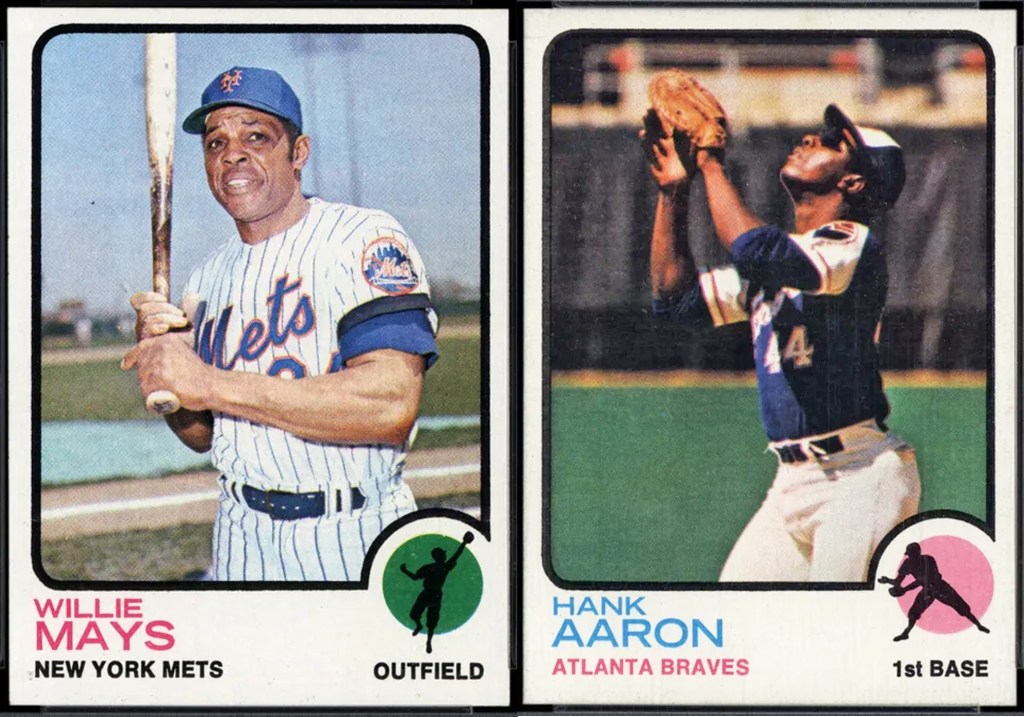

These good action shots helped elevate a card’s status for me. Don’t get me wrong. Finding a Willie Mays in your pack is a great card no matter what he’s doing in the photo. In his 1973 card, for example, Willie poses with a bat and looks sturdy, if a bit out of place, in his pinstriped Mets uniform. Willie has an uncomfortable look on his face. Still, it’s Willie Mays and it’s his last card, so it’s cool. But the Henry Aaron card … so much better. Aaron is seen in game action, close up, fielding a pop fly at first base.

A good action shot makes a card singular, even a cool posed action shot (like Roberto Clemente flipping a baseball in the air for his 1972 card) is dynamite. Unfortunately for Mays, some of his posed shots were repeats. Like, his 1965 and 1968 cards use the same posed photo of Willie looking slightly annoyed. The 1966 and 1969 Mays cards also are repeat photos. But it’s Mays, so they’re worth looking at.

My personal favorite cards to look at would have to be the 1956 Topps set, with the headshot of the ballplayer and the little painted action shot. This is just a beautiful set of cards. I’ve got a handful of them, part of a treasure acquired from one of my big sister’s old boyfriends. His cards were from the 1950s and 1960s, and he had Mays, Mantle, Musial, Koufax, Banks, Robinson (Brooks and Frank, but no Jackie). My 10-year-old eyes popped out of my head while sifting through the shoebox of ancient booty – this was 1970 and the cards were only eight to 15 years old at the time, but goddamn, they seemed like priceless ancient relics to me.

By 1973, we were living in the Atlanta suburbs, and it was just as easy to find stray bottles, and make a quick bike ride to the nearest convenience store to satisfy the baseball card habit. That’s when and where this Bob Oliver came to me. I didn’t know anything about Bob and probably thought he was related to Al Oliver (a Pirates star I’d heard of, in my still-developing baseball brain). They’re not related.

But, thanks to the Interwebs, I discovered something I’d long ago forgotten – Bob Oliver is the father of longtime major league pitcher Darren Oliver! I’ve got one of his cards somewhere, too. Darren played big league ball for 20 years, a good left-handed pitcher for multiple teams who played until he was 42. Bob’s playing career didn’t last near as long, but if you look at the back of his card, you can see he had a few good seasons – particularly in 1970 with the Kansas City Royals. His 1972 output for the Angels wasn’t bad, either.

What stands out for me now when I look at the back of Bob’s card (besides the fact that he had to work in construction to make ends meet during the off-season; he also was a policeman) are those first few lines of his career statistics, telling me where and when he played minor league ball. Gastonia, North Carolina, 1963. Then Kinston, also North Carolina, in 1964. Then Asheville. He was a black kid from California playing in mid-sized cities in the Deep South during the heart of the Civil Rights movement.

When I got this card as a 12-year-old kid, none of what that might imply even occurred to me. It was just a cool baseball card of two guys in what was probably a bang-bang play at first base. When I pulled the card from the shoebox this time and scanned the back, the first thing I wondered was, “what must that have been like? Did Bob Oliver face any kind of racial abuse?” It’s a stupid rhetorical question. Of course, he did. This is America, after all.

“When playing in the minor leagues the racism was overt. It came from the fabric of the community and he felt it deeply,” wrote John Struth in his biography of Oliver for the Society of American Baseball Research. Bob almost gave up; it was that harsh. But moral support from his mother and the kindness of a teammate, Joe Solimine, were saving graces for him.

Segregation was the rule in these North Carolina cities, but he found the resilience to carry on, Struth wrote, “but it left scars. He implicitly pointed fingers at the baseball bureaucracy for its unstated racism. Inferences to reduced opportunities, and different treatment filtered through his thinking and statements.”

Just another heartbreaking experience in baseball’s long history of them.

On the one hand, the Bob Oliver story is one of perseverance and triumph – he did what few can do, he played big league ball and did it well, then watched his son carve out a long and successful career that brought pennants and World Series appearances into the family story before Bob died in 2020. That’s the one hand.

On the other, there is the lingering question we should keep asking, even if it’s a bullshit question designed to keep our eyes looking progressively forward: Why did it have to be that way for Bob Oliver? Why did it have to be that way for anyone in America, in game that had the audacity to call itself the National Pastime?

Here was a big (6-3, 215 pounds) and talented (if misused – he was a natural first baseman, but ballclubs kept experimenting with him in the outfield and at third base), slugging ballplayer. As a young man of 20 he was thrust into the teeth of Jim Crow, experienced the hatred and misguided rage of prejudice, and was forced to carry those unhealthy memories with him for the rest of his life. That’s the other hand.

Nonetheless, his baseball card is pretty cool, and I hope the ghost of Bob Oliver is satisfied with what he accomplished in life.

Other stuff to look at:

- Bob Oliver’s SABR biography

- Elmer Valo’s SABR biography

- Elmer Flick SABR biography

- Beatles Search Yields 1956 Baseball Card Bonanza

******

Johnny Mize P.S.: Long before he became the best left-handed hitter in the National League, the Big Cat was a tennis champion. There simply weren’t enough kids to get up a good game of pickup baseball in Demorest, Georgia, back then. So, Johnny played tennis. He was also a basketball star at Piedmont College. You can read more about this stuff next year with the release of Big Cat: The Life of Baseball Hall of Famer Johnny Mize, published by the University of Nebraska Press.