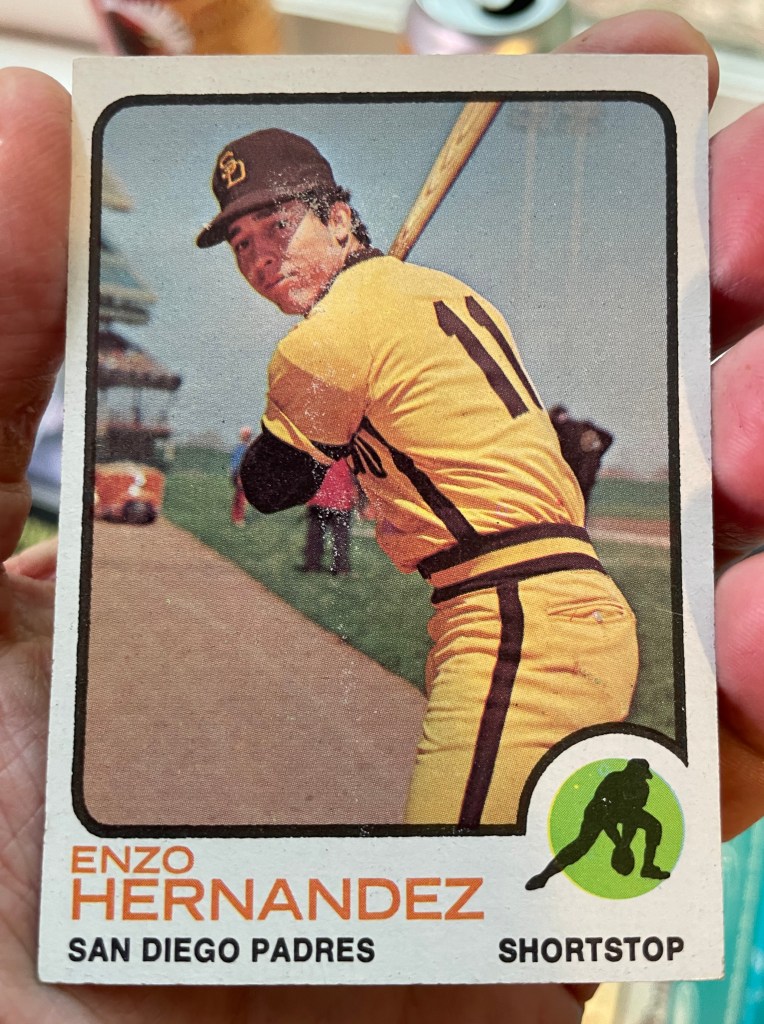

When you look at Enzo Hernández, what do you see? Is this the face of a young man whose quiet confidence shines through his thin smile, a ballplayer looking sharp despite the Padres’ goofy mustard and chocolate uniform? Or – if you look past the scuff and residue from the so-called chewing gum that was packed next to this card – do you see a trace of anxiety, the look of a player who knows he’s sticking around only as long as the team needs an occasionally dependable glove? Maybe it’s both.

The anxiety, the worry, comes into greater focus when you consider Enzo’s tragic ending. He took his own life in 2013, a 63-year-old man struggling with severe depression and failing health.

Perhaps the Hernández we see on this card is thinking of his 1971 season, two years earlier. “Some have called his 1971 season the stuff of legend,” wrote Bruce Markusen shortly after Hernández died. That was the year Enzo set a record by driving in just 12 runs while playing a full season. Though he batted just .222, he managed to get on board often enough to steal 21 bases that year (a Padres record at the time), becoming the first Latin American shortstop to steal more than 20 bases in the National League.

But the next year, 1972, was just as remarkable (look at the back of his card). He was the Padres’ first-string shortstop, but he batted just .195 (he reached base a mere 24 percent of the time). Still, he broke his own club record by stealing 24 bases and led the league in stolen base percentage (he was caught only three times). Enzo was a fast man and probably would have been a great pinch runner or late-innings defensive replacement.

He didn’t strike out often and was tough to double up because of his speed, and if he’d been a slightly better hitter or drew more walks, he would have been a terrific threat, possibly a good leadoff hitter. He stole a career-high 37 bases in 1974. But he soon began suffering from back injuries which eventually led to surgery. The operation was a success, but not successful enough, apparently – the Padres released him during spring training of 1978 (the rookie season of a new sensational shortstop in San Diego, a kid named Ozzie Smith).

The Los Angeles Dodgers signed Enzo, but after playing well for the Class AAA team in Albuquerque for most of 1978, he finished his big-league career, playing four games for the Dodgers that year. He played one more season of pro ball in Venezuela – his 11th season – and seemed to have recovered from his injuries. But then he just disappeared, blending into the fabric of family life in the city of El Tigre, and a family pharmacy business.

Hernández had been part of a second wave of ballyhooed shortstops from Venezuela, he and Dave Concepcion following in the footsteps of Chico Carasquel and Luis Aparicio. “Venezuela began to be seen as the cradle of the shortstop,” wrote Nelson Julián Morales Álvarez in his biography of Hernández for the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR).

Enzo was considered a good gloveman, yet he led the league in errors one year. Still, he managed to journey from his childhood on a farm in Venezuela to the big show, becoming the first everyday shortstop in San Diego Padres history, overcoming an anemic bat long enough to play parts of eight seasons as a major leaguer. But it wasn’t enough to sustain him. Hernández made the news again in January 2013 after taking an overdose of painkillers.

“Over the last year, Hernández struggled with depression, for reasons that remain unknown to the public,” Markusen wrote for The Hardball Times in January 2013. “I only hope that his death spurs additional research into the lives of major leaguers after their careers have ended. It is a subject worth exploring.”

It was worth exploring back when Bruce wrote his excellent story, and it still is.

To dive a bit deeper into the life and career of Enzo Hernández, check out the SABR biography by Álvarez and Bruce Markusen’s story in The Hardball Times.

******

Johnny Mize P.S.: The Big Cat from Demorest (known as the Demorest Destroyer to legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice) is the only player in big league history to hit an (intentionally) yellow baseball for a home run. Color spectrum experts had claimed that yellow was the most visible of all colors, so yellow baseballs were used in a 1938 game between the Cardinals and Giants, and Mize, playing for the Cardinals, smacked one out of the Polo Grounds. Stay tuned for Big Cat: The Life of Baseball Hall of Famer Johnny Mize, Spring 2024 from University of Nebraska Press.